Jump To:

Artist Deborah Aschheim has installed a selection of Raleigh Stories portraits at Walnut Creek Wetland Center. The portraits include park patrons and residents of the nearby neighborhoods. You can find the portraits in the two meeting rooms at the community center and visit during park hours.

View the portraits and read the stories below.

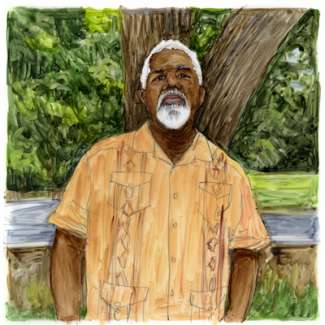

George C. Jones

George C. Jones, Jr., the Executive Director of Partners for Environmental Justice, grew up in Biltmore Hills and is a longtime member of St. Ambrose Episcopal Church. He is working to honor Dr. Norman Camp’s vision for WCWP while he leads PEJ into the next era of environmental stewardship and restoration.

I am the Executive Director of Partners for Environmental Justice. I've been in a nonprofit management for over 10 years.

I grew up in Biltmore Hills. My parents built our house at 2008 Gilliam Lane, it was their first home. My father was the assistant principal at Carnage Middle School. The area behind the

Wetland Center was like a backyard for me. I had an appreciation for outdoors growing up. I also experienced flood area activities.

I've been baptized, married and confirmed in St. Ambrose Episcopal Church.

Norman and Betty Camp were members of St. Ambrose. In the early 1990s, church and community leaders came together to say to the City of Raleigh, we've got to do something about the dumping, the degradation of the creek bed. We don't have enough investment in this community to protect people's lives and livelihoods.

Partners for Environmental Justice was formed out of three churches: Trinity Episcopal Church in Fuquay-Varina, St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Cary, and St. Ambrose. St. Ambrose supported Dr. Camp’s leadership and his priority of educating the community about the importance of the habitat and wetland protection of Walnut Creek.

Trust issues between the city and residents go back to the building of the first Black subdivisions in Raleigh. They designated the first neighborhoods for African Americans in a floodplain area. In the early 20th century, the area along Walnut Creek was a junkyard full of trucks and vehicles. Walnut Creek has high nutrients and chemical toxins that come off the streets and flow into the creek beds, and those contaminate the wetlands.

When Norman Camp visualized the Center, it was an opportunity to put a flag in the air and say, we live here, we care about our community, we’re not going anywhere. We want Walnut Creek to be a part of the solution to build a better model.

Some of the solutions we’re promoting in community partnerships are individual scale solutions, like using cisterns at your home that filter water for gardening or removing impervious surfaces like asphalt driveways and replacing them with porous surfaces. Some solutions require investment from the city or even federal government.

Raleigh is one of the fastest growing communities in the country. Targeted economic development really can only expand south and southeast of downtown into historically Black neighborhoods, adjacent to the Walnut Creek Watershed. I think equitable development would be making sure that any displacement is done in a way that's environmentally and economically beneficial to the residents living in the community.

The benefit of having the WCWP here, as an example of infrastructure improvement, is to address the degradation of the streams and creeks, the dumping and debris in the watershed, and the history of raw sewage and contamination to water quality, particularly affecting minority communities. It becomes a working experiment and demonstration of what can and should be done in helping to address the problem.

Harold Mallete

Harold Mallette grew up in Biltmore Hills, moving to Waters Drive shortly after the neighborhood was developed. His concern for environmental justice grew out of his parents’ friendship with Dr. Norman and Betty Camp.

I’ve been a mental health, family counselor, and then a substance abuse counselor. Now I do juvenile justice counseling. There’s always been an ethos of service in my family.

I am the son of David and Mary Mallette. My parents were educators out of Robeson County, and then Wilmington. We moved here from Wilmington when I was seven, in 1967. My father and Dr. Norman Camp were friends, along with Carolyn Winters with the environmental people. They help to initiate concern about the Wetland Park.

First of all, nobody was calling it “wetland,” it was sewage. It ended where State Street comes down to Bunche Drive, at a big pipe, and sewage and water ran through that. As kids we played in little platoons of concrete. We would go out in those little platoons and ride up and down the water.

Q: Was it unhealthy, though?

H: Definitely.

We did not know how unhealthy it was. It was a part of play growing up. As we became teens, we became more and more aware that this is really sewage. Most of the time it didn’t smell bad. It looked weird. Green, Brown. But the water, because of the elevation, would often come in and flush that all out so it looked like regular water. The adults began to talk about it. As the water began to come regularly, it threatened to flood the church.

We belonged to St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Wilmington, it was the first African American Episcopal Church in North Carolina. We came to St. Ambrose in 1967 or 68. I went to Fuller Elementary. This whole neighborhood was 3 or 4 four years old. It was something to really be proud of, it still is.

I had never seen a neighborhood specifically developed and planned for African American homeowners. In some neighborhoods, there may be 10 or 20 houses owned by African Americans. But there were at least 100 houses in Biltmore Hills and Rochester Heights. It was something to behold. It was a real, thriving community at that time. There was a grocery store, 2 gas stations, a cleaner.

Most of the homeowners were veterans who had lived in different parts of Raleigh, and they finally gotten to where they could utilize the GI Bill to get financing. That's how this neighborhood developed.

Desiree Bolling

Desiree Bolling is a member of St. Ambrose Congregation and an advocate for those who don’t have a voice, with a focus on health. She served under four North Carolina Governors on boards for Developmental Disabilities and Autism, and advocates for people who are blind or have low vision.

I moved to Raleigh when I was about 50. I knew my purpose was to be an advocate in the community. I started getting involved with “Project DIRECT” (Diabetes Intervention Reaching and Educating Communities Together, a program of the Federal Center for Disease Control) which continued as the nonprofit “Strengthening the Black Family”. I was involved in raising awareness of health priorities and chronic diseases that particularly affect the Black community.

My focus is health. I served under four North Carolina Governors on boards for Developmental Disabilities and Autism. I advocate for those who don't have a voice.

I also advocate for people who are blind and with low vision. I decided to be a voice and a mentor, and speak out, and the only way I could do it, I had to start with myself. People are not educated about these disabilities, so I use myself as a model. As a child, I was diagnosed with childhood glaucoma. A lot of people lose their vision now due to diabetes. They have a really, really, really hard time adjusting.

At the health center, I do a vision education day. If a patient calls and says, I can’t take my blood sugar, I encourage them to use the tools they have, like large print outs, getting a blood pressure monitor, trying to help people change their eating habits and their lifestyle.

I live in Southeast Raleigh not too far from St. Ambrose. I went with a friend to St. Ambrose and it was the first time I really felt, this is the right place. Father Taylor sees my independence and he knows I will try to work things out before I will ask for help.

At St. Ambrose, I am really proud and excited about the Labyrinth. I hear the birds, I can still hear a little bit of traffic, but I just tune into nature. Even though I can’t see, I hear and see and feel. It’s a kind of sight. The Labyrinth gives you spiritual direction, you’re close to nature but you’re close to God, you can feel His presence and shut everything out around you.

You can get this from nature too. At Walnut Creek, sitting outside with just a little wind, I could really appreciate hearing people engaged around me and the beauty of it.